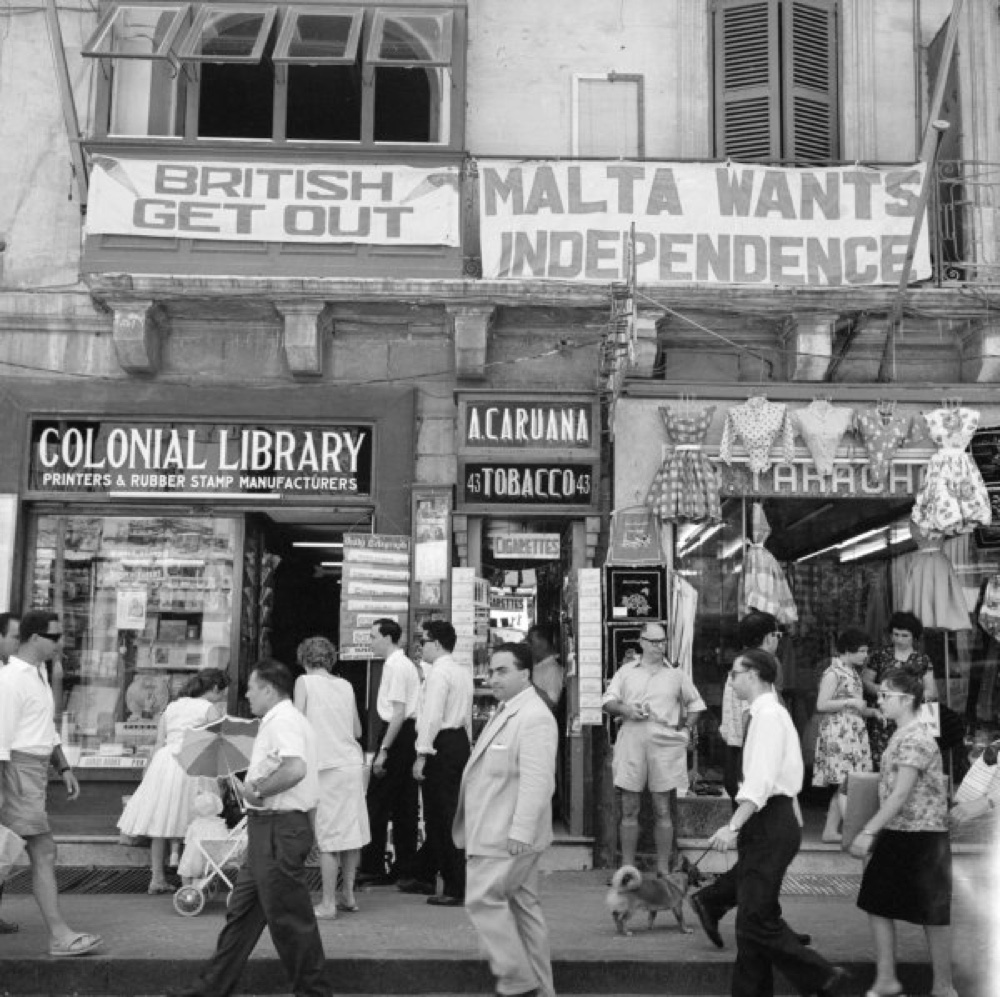

The Sette Giugno Uprising, By Pen Lister. March 19, 2018. Categories: Maltese Democracy Tags: malta

The Uprising

- The first spark of unrest centred on the Maltese flag defaced with the Union Jack flying above the shop “A la Ville de Londres.” The death of the President of the Court some days earlier had required all governmental departments to fly the Union Flag at half mast, including the National Library buildings in Pjazza Regina, and the meteorological office.

- The crowd moved on to the meteorological offices , housed in a Royal Air Force turret. After breaking the glass panes, the mob entered the offices ransacking and destroying everything inside. Some individuals climbed onto the turret, removing the Union Jack and throwing it into the street. The crowd burned the flag along with furniture taken from the offices nearby.

- The mob then moved back to Palace square , where they began to insult the soldiers detached in front the Main Guard buildings. The officer that was responsible for the watch closed the doors of the building and those of the Magisterial Palace across the square.

- In Old Theatre street , the offices of the Daily Malta Chronicle were broken into. Pieces of metal were placed to jam the printing machines. Ten soldiers, led by Lieutenant Shields, approached the offices of the Chronicle. These were surrounded by a crowd which then began to throw stones and other objects at the soldiers.

-

While this was taking place, other crowds were attacking the home of Anthony Cassar Torreggiani in Old Bakery street perceived as supporters of the Imperial government and profiteering merchant. Here six soldiers were trying to stem a crowd of thousands. They broke and opened fire killing the first victim of the uprising, Manwel Attard, fell in front of the Cassar Torregiani house.

- Meanwhile, in the Chronicle offices, an officer ordered his men outside, since there was an evident smell of gas in the building. To clear a way out, the officer ordered a soldier to shoot low, away from the crowd. This shot hit Lorenzo Dyer, who tried to run away.

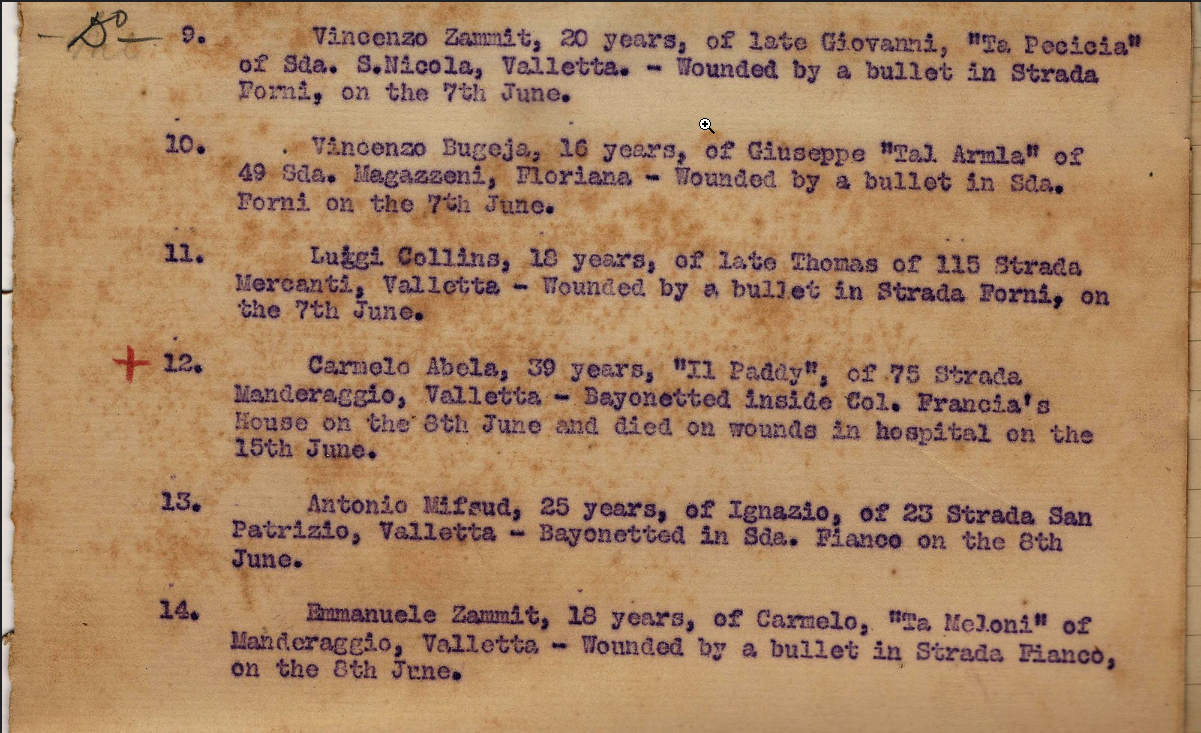

- On 8 th June the crowd attacked the palace of Colonel Francia , the owner of a flour-milling machine. The Royal Malta Artillery soldiers protecting Francia’s house were reluctant to use force against their own countrymen. The crowd forced its way in and threw furniture, silverware and other objects outside. In the evening, one hundred and forty navy marines arrived, clearing the house and street of crowds. Carmelo Abela was in one of the side doorways of Francia’s house, calling for his son. Two marines proceeded to arrest him, and when he resisted, a marine ran him through the stomach with a bayonet. Abela died on June 16.

The report of the inquiring commission then proceeded to state that a shot was heard from the direction of a window of the Cassar Torreggiani house. At face value, this gives the impression that the Maltese were the first to shoot during the uprising. At that moment, as eyewitnesses reported, one of the soldiers shot a round into the crowd, with the rest of the troop following. The first victim of the uprising, Manwel Attard, fell in front of the Cassar Torregiani house. Other individuals were injured. Ġużè Bajada was hit near Old Theatre street, and fell on top of the Maltese flag he was carrying. The officer in charge began shouting for the firing to cease. Meanwhile, in the Chronicle offices, Lieutenant Shields ordered his men outside, since there was an evident smell of gas in the building. Shields feared making the soldiers exit the office one by one, since the crowd outside would certainly attack them; on the other hand, they could not remain inside. To clear a way out, Shields ordered a soldier to shoot low, away from the crowd. This shot hit Lorenzo Dyer, who tried to run away. Since the injury was serious, he was lifted by the crowd and carried to Palace square. During this initial uprising, three died and fifty were injured.

List of persons that were wounded or killed during the riots of the 7th and 8th June 1919 (detail, part 1/3). Other images in this series are available from National Archves of Malta, used with kind permission.

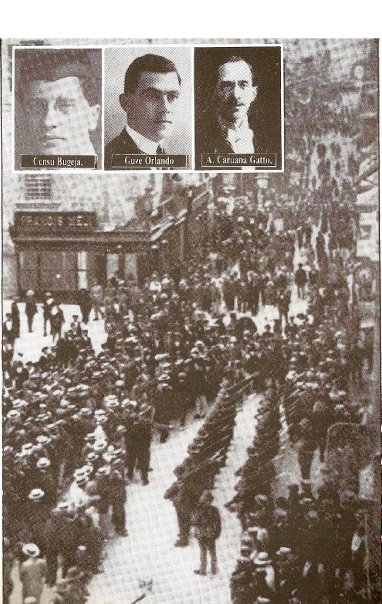

Image Caption: Newspaper clipping of the time, linked from Maltese History and Heritage. Image credit: https://vassallohistory 7th/8th June 1919 jpg

The proceedings in the National Assembly were interrupted as persons injured in the streets were brought inside. Some of the delegates left the buildings, while others ran to the balcony. The Assembly passed a quick motion in order to have a resolution to present to the Imperial government. Count Alfredo Caruana Gatto then addressed the crowds, asking them to restrain themselves from further violence. The Assembly then sent a delegation to the Lieutenant Governor, asking for the troops to be removed for the crowds to retreat. The Governor accepted, and Caruana Gatto addressed the crowd again, which complied and began to fall back.

The day after the attack, censorship was reinstated for political articles. In the morning, flowers and other tributes were placed in the streets where the victims had died. The deaths and injuries of so many people did not halt the uprisings. Another group attacked the flour mills owned by Cassar Torreggiani in Marsa, while other trading houses were raided in the outlying villages.

Substantial parts of this text have been drawn from Maltese History and Heritage, a project by Vassalomalta. Com. Usage permission TBC.

Links

- Malta Diary Sette Gungio 1919 – the Maltese rebel against British Rule and The Establishment (great images in this post): http://b-c-ing-u.com/2017/06/21/malta-diary-sette-gungio-1919-maltese-rebel-british-rule-establishment/

- An alternate view: “The Sette Giugno Myth”: https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20170607/opinion/The-Sette-Giugno-myth.650126

Sources

https://vassallohistory.wordpress.com/uprisings-revolts/ http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2013-06-08/leader/the-story-of-sette-giugno-1778679808/

Featured Image: Sette Giugno, detail. By penworks CC BY SA

Sette Giugno: Context and Significance

The Context – The difficult times after WW 1

After WW 1, the Maltese colonial government failed to provide an adequate supply of basic food, imports were limited, food became scarce and the cost of living increased dramatically.

The wage of dockyard and government workers was inadequate to keep with the increase in the cost of food. The dockyard workers formed a union in 1916, and in 1917 organised a strike after being offered a ten per cent pay increase which was considered too small to keep up with the cost of living.

People believed that grain importers and flour millers were making excessive profits over the price of bread. Merchants controlling other commodities also made large profits from the war, in spite of price regulations.

On the political side the first meeting of the National Assembly, held on February 25, 1919, approved a resolution demanding independence from the British Empire.

This difficult situation gave rise to extremism. Crowds took to the streets attacking wealthy people perceived as close to the colonial government.

Significance of the 7th June Riots

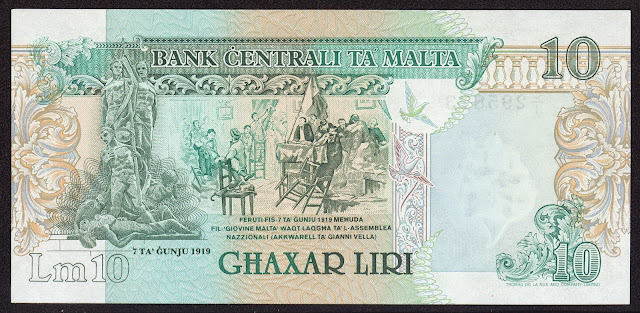

Image Caption: Reverse 10 Lira bank note, Malta, 1989.

The resistance and support for the pro-Italian parties that had challenged the British presence on the island increased.

Considered as the first step towards Maltese Independence. In fact:

- The new Governor, Lord Plumer, recommended liberal concessions to the Maltese.

- The House of Commons of the United Kingdom stressed that Malta was to have “control of purely local affairs”

- The Colonial Secretary sent a detailed description of the proposed constitution to the National Assembly. On April 30, 1921, the Amery-Milner Constitution was proclaimed.

- Political censorship enforced after the uprising was repealed on June 15, 1921.

- The first election held under the new constitution was held in October 1921, with the Prince of Wales inaugurating the new representative chambers on November 1, 1921.

Honouring the Fallen

Addolorata Cemetery. By Frank Vincentz (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons

The bodies of the four victims of the Sette Giugno were placed in their tomb in the Addolorata Cemetery on November 9, 1924. On that occasion the Italian Fascist government celebrated the four victims as “martyrs” of the Italian Risorgimento and heroes of the Italian irredentism in Malta.

On June 7, 1986 the Sette Giugno monument was inaugurated at St George Square (Palace Square), Valletta. The Maltese Parliament declared the day to be one of the five national days of the island, on March 21, 1989, with the first official remembrance of the day occurring on June 7, 1989.

Substantial parts of this text have been drawn from Maltese History and Heritage , a project by Vassalomalta. Com. Usage permission TBC

Sources

- Featured Imnage: penworks CCBYNCSA

- List of dead or wounded, from The National Archives of Malta Flickr account.

- WW1 disembarkation: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld_War_One%3B_wagons_for_disembarkation_in_Malta_Wellcome_L0064610.jpg

- Addolorata: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malta_-_Paola_-_Addolorata_Cemetery_10_ies.jpg

- Bank Note: Aquarell of Gianni Vella. On June 7, 1919, Vella was at the Circolo La Giovine Malta in St Lucy Street, Valletta, where the Assemblea Nazionale was discussing a course of action in its dealings with the British colonial government. Source:http://www.worldbanknotescoins.com/2015/05/malta-10-maltese-lira-banknote-1989.html